Motor-memory can often be overlooked when we are thinking of helping children and young people to spell accurately. We will work on visual activities directly intended to embed words in their memories – such as ‘look, cover, write, check,’ where pupils memorise a word, cover it up, write it out and then check their spelling – and ask questions such as, “Does it look right?” But we don’t often ask if it ‘feels’ right.

When children are first learning to read we focus on phonics for decoding, isolating the separate sounds that make up a word. We then reverse that approach to build words, often sounding out the segments and asking them how we will express that on the page. The word ‘Church,’ for instance, will become, ‘Chu, er, chu.’

So we have approaches that focus on the visual memory, and others on the aural memory, but we often neglect to focus on the motor-memory. How a word feels as we inscribe it. It is one of the reasons for encouraging those who are struggling with spelling to use cursive – ‘joined up’ – handwriting. The theory is that instead of the word being a series of separate letters the brain needs to recollect and reproduce, it becomes one, fluent, movement. For instance, ‘heavy,’ is no longer, ‘H, E, A, V, Y’ – five elements to remember how to scribe, but ‘heavy’ one, continuous, sweep along the line.

This theory has been built in to programs that teach touch-typing, so that by employing the frequent repetition necessary to learn to use the keyboard without looking at it, learners begin to put down words on the screen without having to think about the letters in them. They spell by using the memory in their movements.

One of the earliest resources to use this was Touch, Type, Read and Spell (TTRS). Originally it was a standard touch-typing course involving copying from books that differed from offerings such as those from City and Guilds, by using real words in its exercises instead of drills focused on letter groupings on the keyboard.

One of the earliest resources to use this was Touch, Type, Read and Spell (TTRS). Originally it was a standard touch-typing course involving copying from books that differed from offerings such as those from City and Guilds, by using real words in its exercises instead of drills focused on letter groupings on the keyboard.

Then along came personal computers and approaches like Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing. Whilst it took its time, TTRS eventually went online to become www.readandspell.com . Now available for individuals to use at home, or for whole tranches of pupils to use at school, it still uses as its core vocabulary list the ever influential ‘Alpha to Omega’ spelling course, originally devised to teach dyslexic learners in the 1980s.

It is not the only program to do this. Kaz (www.kaz-type.com) is a system structured i n a similar way. Although originally targeted at general learners, it has adapted to include more specialist elements, with features such as the ability to change the font and its size, and or to select a colour scheme that a user might find easier to read on screen.

n a similar way. Although originally targeted at general learners, it has adapted to include more specialist elements, with features such as the ability to change the font and its size, and or to select a colour scheme that a user might find easier to read on screen.

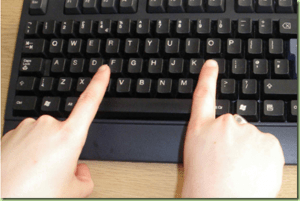

The important element of this approach to spelling, however, is keyboard fluency. As Kaz point out on their website, “Typing with 2 fingers uses the conscious mind but when you touch type with all your fingers and thumbs, the skill is transferred to the subconscious – leaving the conscious mind free for creative writing and the task at hand.”

The important element of this approach to spelling, however, is keyboard fluency. As Kaz point out on their website, “Typing with 2 fingers uses the conscious mind but when you touch type with all your fingers and thumbs, the skill is transferred to the subconscious – leaving the conscious mind free for creative writing and the task at hand.”

There are compelling arguments for all children and young people to learn to touch-type. Removing barriers to their creativity, and helping them too become more productive, is just one more.